18 Oct 2016

Every five minutes, someone, somewhere, says that “markets hate uncertainty”. This is an example of anthropomorphism or the attribution of human characteristics to animals, objects or ideas.

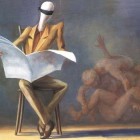

Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing according to Warren Buffet, wrote about Mr Market, an obliging business partner who offers to buy you out or sell you a larger stake on a daily basis. Mr Market can be generous or miserly but his defining characteristic is that he always shows up. Mr Market is in fact, a market.

Regrettably, the temptation to turn Mr Market into a soap opera character who experiences human emotions has proved too much for many commentators. Watch, read or listen to today’s news and you will find that Mr Market is an extremely judgmental fellow. Donald Trump makes him very unhappy. He is incandescent with anger about Brexit.

Interestingly, Mr Market is not a great believer in democracy. When he thinks that voters in the US or the UK are making a mistake he stamps his foot in rage. He much prefers the smack of firm leadership. When Saudi Arabia, Iran and Russia attempt to collude to restrict the supply of oil he performs a little jump of joy.

Enough. Mr Market does love or hate anything. Markets are just places where buyers and sellers look for each other and sometimes meet. If you want to attach a smiley face to the chart of a rising market that’s up to you but remember that higher prices result in losers as well as winners. Witness the UK housing market – oldies = smiley face: youngsters = sad face.

The sloppy thinking that leads people to say that markets hate uncertainty invariably evolves into the confident factual statement that “investors hate uncertainty”. This assertion is central to the fund management industry that wants to frighten you into paying to have your savings looked after. Please see my post “Clients are very nervous”.

But the truth is the opposite. Investors love uncertainty because it causes assets to be mispriced. It is only the mispricing of assets that leads to good opportunities to buy and sell.

I don’t want to be unkind but if someone says that they fear uncertainty that are metaphorically wearing a tee shirt that says “I am a loser”. On the back it says “Please charge me a large fee for looking after my money”.

Fear of uncertainty leads people to play outcomes rather than probabilities.

You hear on the financial news or on a financial channel that someone (an expert, no doubt) thinks that the outlook for the oil price is terrible. (He realises this now having watched in silence as it halved from last year’s high). Here is a list of nations that export oil, here are the companies that drill for oil and those that store and refine it. Oh dear, oh dear.

If you are wearing the Loser T shirt you will fret and decide either to redesign your investments to insulate you from the day when the world stops using oil completely or (more likely) you will swiftly hand the management of your beleaguered savings over to an expert like the one on TV.

If you are a real investor you will snuffle quietly like a truffle hunting animal. And once you have blown your nose here is what you will say to yourself.

That expert has talked plausibly about OPEC, barrels, stocks, sanctions, oil sands, gas futures, climate change and electric cars. He has clearly learnt to sound as if he knows what he is talking about. Let’s acknowledge that, in line with the law of averages he is occasionally right or, more likely, wrong. It makes no difference to me. What I want to know is what are asset prices telling me?

Is Royal Dutch (for example) trading like a company in mortal danger? If its share price says that everything is absolutely fine I might consider selling it because there might be a risk that the shares are not reflecting. But if the price is already at highly distressed levels, with a dividend yield that is so generous that it is obvious that the market doubts that the pay-out to shareholders will be maintained, then it merits some investigation as a potential buy. How does the potential reward compare to the risk?

And that’s it. Out in the real world the direction of the oil price is important for all sorts of reasons, half of which are unknown to me. Also there will be all sorts of opinions, none of which really matter. Because the important consideration for an investor starts with the price of the asset and leads to the question: how plausible is the outcome that is implied by the price of this asset?

Uncertainty is baked into that question. Without uncertainty, that question would have no meaning and no use.

Postscript

As I write today the words “Brexit” and “uncertainty” are linked so often that, if translated into German they would doubtless become a single word (Britischerausfahrtunsicherheit, or something like that). This apparent craving for certainty – which is probably the bogus posturing of bad losers – is beyond the scope of normal human understanding. It is a thought process that can never be satisfied save perhaps by recourse to a god who will offer comfort if asked nicely.

This general howl of frustration is of no use to investors. It is a truism that very little is known about the future. That’s why most predictions merely model the recent past.

It is also true, in my view, that democratic politicians can only affect asset prices by ceasing to be democratic. So if we hear suggestions that foreigners’ rights to own British assets should be restricted or that the referendum result itself should be overturned by politicians, elected and unelected, we should take note.

Other than that, it’s just noise.